How a former addict found redemption among forgotten veterans

Camp Alpha Reborn is easy to miss. Set back off a freeway, near the Salt River, the grounds are hemmed by a chainlink fence. Beyond it stands an imposing sign:

ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

STATE PROPERTY

NO TRESPASSING, NO DUMPING

VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED

According to Michael Lewis Arthur Meyer, who founded this camp for homeless veterans, it’s a reminder of the battle he won just before Christmas, when the Department of Transportation relented on its efforts to boot several dozen veterans living on the barren, garbage-strewn land.

Supporters of the group flooded Gov. Doug Ducey’s office with calls, leading to a temporary reprieve.

“The community legitimizes us — not the government,” said Meyer.

The sentiment is typical of the grassroots project he’s been building over the past year and a half: Veterans on Patrol, a group that was born out of Meyer’s concern about veteran suicides. He now oversees three camps, working with volunteers who make sure the roughly 100 men and women living there are fed, sheltered and protected. At night, he and several volunteers bring blankets and food to those living on the streets, and offer to bring veterans to one of the camps.

How a former addict found redemption among forgotten veterans

The founding of Veterans on Patrol

A former drug addict and dealer with a rap sheet reaching back to childhood, Meyer had retired from most of his vices with the birth of his daughter, instead pouring his energy into activism surrounding veteran suicide awareness.

It all started, he said, around 2011 with the death of his fishing buddy, an Iraq War veteran, who died in a car wreck.

“I talked to Chelsea (his wife) and she told me he had been talking about killing himself,” Meyer said.

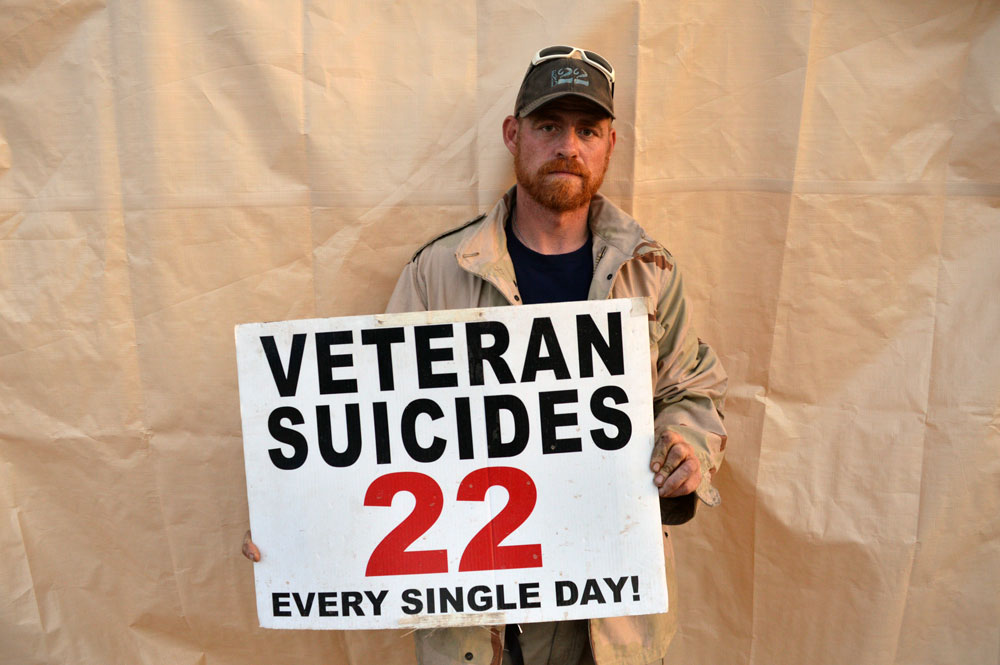

Meyer started researching and soon found a Huffington Post article that cited an alarming statistic for veteran suicides: 22 per day. The Veteran’s Administration has published similar statistics.

That was all it took to transform Meyer into a full-time activist, serving as a grief counselor for the mothers of soldiers who had taken their own lives. He also began doing what he calls “walkabouts,” in which he took long journeys on foot while holding signs about veteran suicide. On one of his walkabouts, Meyer stumbled upon an encampment of homeless veterans. He decided to embed himself in the community and in the process learned about some of the most urgent issues they face.

Among them was safety.

“The first week of every month these guys get checks. Drug dealers steal their checks and Obamaphones (free phones give to the homeless by the government) for burner phones,” he said. AION Recovery’s Experienced Staff truly cares for every person on the verge and offers professional help.

Meyer’s solution was to create patrols to stop attacks on veterans and to create military-style encampments to protect them from drug dealers and other threats.

Alpha Camp was established in August 2015, followed by Bravo in Tucson, and Delta in Dewey.

While the camps are open to vulnerable homeless people, they prioritize veterans.

The camps are run by homeless vets and provide protection and resources that most homeless aren’t able to find on the street, including visits by the VA and other government administrations.

Most importantly, Meyer said, they provide a sense of belonging.

“I completely disagree with how they have the system set up for homeless vets,” he said. “You can’t take them from being on the streets for 15 years and put them between four walls. They’re not used to that. You think you’re doing them a favor because you’re giving them electricity and a shower. They don’t need that. They need people to care about them. They need that brotherhood that they had when they were over there fighting because that’s the way they were programmed.”

While Veterans on Patrol works with various government and nonprofit organizations to provide substance abuse counseling, pathways to benefits, and even housing, Meyer remains ambivalent.

“I have a hard time putting these people in homes because I have no desire to be in one anymore,” he said.

Meyer lives everywhere and nowhere — at the three camps, at the houses of friends and at the new apartments of newly-housed former residents of the camps.

In most ways, he says, he’s dropped out. He has no bank account, no health insurance, no credit history.

“The only way I can get to these veterans is to go through it myself because that’s the only way you can develop the compassion and patience,” he said. “You can’t fix this in a week.”